Monkey Man — The inclusion of the Hijra community in the vedas.

Dev Patel’s directorial debut, Monkey Man, stands as the most visceral depiction of a revenge action to grace the silver screen this year. His vision for the movie is ambitious, blending elements of traditional Indian storytelling of jaya with gritty sequences reminiscent of action blockbusters like ‘The Raid’ (2011). The film’s protagonist, played by Patel himself, is an unnamed fighter, occasionally referred to as ‘Kid.’ This is a character whose arc is meant to mirror the struggles of victims from marginalised communities in modern-day India. From the brutal police commissioner Rana Singh, the sex trafficker Queenie Kapoor, to the fraudulent religious leader Baba Shakti, all serve as a symbol of corruption that continues to plague.

However, despite its lofty aspirations, Monkey Man occasionally stumbles in its execution. The film’s political commentary, while relevant, feels somewhat superficial towards the ending, lacking the depth needed to fully close themes they open. Yet, for all its flaws, the movie remains an exhilarating experience considering Dev Patel figuratively and literally puts his blood and sweat into every frame. However, the most striking aspect remains the movie’s incorporation of the Hijra community, India’s trans population, who play a pivotal role in the protagonist’s development.

In India the Hijras are both people born intersex and people who choose to undergo a castration ceremony, removing their male genitalia as an offering to Hindu goddess Bahuchara Mata. Most hijras consider themselves to be a different gender altogether — neither male, female, nor transitioning. It is with their introduction that the movie shift’s itself more towards philosophy keen to rebirth and purpose. In Monkey man, Kid, much like every hero, soon faces the second act fall, the product of his initial plan. The training montage in Monkey Man is mentored by Alpha, the keeper of a secluded temple inhabited by Hijras, where the protagonist regains strength and solace amongst a group whose resilience starkly contrasts the oppression they face. Although the hijra community’s evolution was restrained within the era of the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526) and the Mughal Empire (1526–1707), historically, hijras have been a part of our society for centuries, with mentions dating back vedic inscriptions.

“Beautiful. Isn’t she? Parvati and Shiva. One half devotion, the other destruction. Male. Female. Neither. Both. Some people find that strange, but we hijras understand it completely” — This was Alpha’s first dialogue in the movie. The idol he speaks of is Ardhanarishvara, a composite deity represented by the hindu god of destruction, Shiva and his consort, Goddess Parvati. Among the various manifestations of Parashiva, Ardhanarishvara stands out as exceptionally distinctive. In this portrayal, the figure seamlessly combines both masculine and feminine attributes. On the right half of the form, characteristic of the male aspect, traditional ornaments adorn the body. Matted locks of hair, reminiscent of asceticism, partially cover one side of the head, while a third eye, spiritual insight, is partially visible on the forehead. The loins are modestly covered with a tiger skin, a symbol of primal power and mastery over the animal world.

Conversely, the left half of the figure embodies feminine traits. The hair is neatly combed, indicating care and adornment. A tilak, a religious mark worn on the forehead, adorns one side, showing devotion and auspiciousness. The body is draped in a silk garment held together with girdles, representing grace and elegance. An anklet adorns the ankle, adding a touch of femininity and adornment. Additionally, the foot is coloured red with henna, a traditional adornment signifying beauty and fertility. The symbolism behind Ardhanarishvara goes beyond mere representation; it signifies the intrinsic unity and interdependence of masculine and feminine principles in the cosmos. By embodying both aspects within a single form, the avatara highlights the complementary nature of gender duality and balance between opposing forces, serving as a metaphor for the interconnectedness of all dualities, including but not limited to gender.

It is theorised that the early depiction of Ardhanarishvara may have drawn inspiration from Vedic literature, particularly the composite figure of Yama-Yami, which combines the primordial Creator Vishvarupa with Agni Deva. This amalgamation is symbolised as a bull that also embodies feminine aspects akin to a cow. Interestingly, a parallel to this androgynous concept is found in Greek mythology, such as in the figures of Hermaphroditus and Agdistis. While, a precursor to Ardhanarishvara is mentioned in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, which describes the first being as a unified entity of both male and female, resembling a closely embracing man and woman. This being then divided into two, giving rise to the creation of a husband and wife.

The essence of this idol lies not in the longing for two separate individuals to reunite, but rather in the longing for the convergence of two fundamental dimensions of existence — both external and internal. In this perspective Shiva incorporates the feminine aspect as an integral part of himself, manifesting as a being that is simultaneously half-woman and half-man to convey that true betterment occurs when one transcends conventional gender binaries, embodying both masculine and feminine qualities in harmony. It’s not about becoming a neutral entity but rather about embracing the entirety of human experience — being fully man and fully woman. From a strictly orthodox interpretation of dharma, the hijra people may not fit neatly into the prescribed gender roles and societal norms. However, interpretations of dharma have evolved over time, and many modern Hindus advocate for inclusivity and compassion, viewing the hijra community as deserving of respect and dignity like any other group. This need not be viewed as skewed development, to some people it was only when these two qualities balance that they feel fulfilment.

Hermaphrodite icons like Ardhanarishvara are often interpreted across various cultures as representations of fertility and the concept of boundless growth. The image of Shiva embracing Parvati, embodying both masculine and feminine aspects, mirrors the prolific reproductive potential attributed to Mother Nature. This suggests a unity where supposedly opposing forces like male and female energy, merge seamlessly into a non-dual state. In this oneness, the distinction becomes so blurred that it’s nearly impossible to discern one from the other, understanding the interdependence of all aspects of existence.

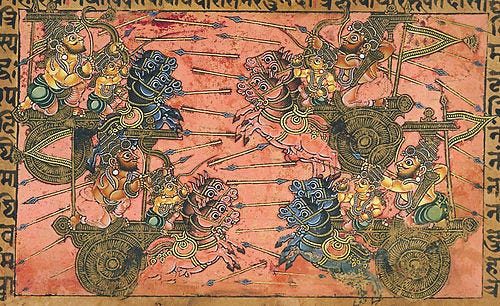

In the mahabharata there are various nods towards the Hijras, a clear one being the trans character of Shikandi. As per the Adi Parva, during Shantanu’s reign over Hastinapura, Bhishma was ordered to conquer the three princesses of Kashi, Amba, Ambika and Ambalika. They were to be betrothed to the crown prince Vichitravirya. In the Ambopakhyanaparvan chapter of the book Udyoga Parva of the Mahabharata, the rest of Amba’s tale is narrated by Bhishma when Duryodhana questions him as to why he did not kill Shikhandi, an ally of the Pandavas. Learning of Amba’s illicit relationship with the King of Salva prior to a wedding, Vichitravirya rejected her to be his bride.

Amba had hoped to marry Salva, but as she was won by Bhishma, he too rejected her out of kshatriya pride. Not to lose her worth as a partner, which during the time was all a princess was destined for, she pleaded with bhisma to wed her, exclaiming that her alternative was suicide. Bhisma by not choosing to break his vow of celibacy, bent and denied her request. This further infuriated Amba further, as she had now been spurned by three men to their will. She reflected on her misfortune, and held Bhishma accountable. Despite counsel to return to her father, Amba resolved to seek Parashurama’s help. Regardless, when Parashurama demanded Bhishma marry Amba, he refused again, only leading to a battle spanning twenty three days just to end in a draw. Once again, Amba was urged by another man to let go, but she vowed to achieve her revenge through devotion.

Amba performed austerities and pleased Kartikeya, the god of war and Shiva’s son. He granted her a garland of ever-fresh lotuses and declared that whoever wore it would destroy Bhishma. With this garland, Amba made one more attempt to seek help from many kings and princes to support her in her just cause. However, there was no response from any of them to help her as they did not wish to compete with Bhishma. In a final effort she approached Drupada but even he declined; in frustration she cast the garland off on a pillar outside Drupada’s palace and chose death. No one had dared to touch the ‘cursed’ garland, however as a calling Drupada’s first daughter, Shikandi was the one to put it on. She felt and was raised from then to be a man whose sole purpose towards the kurukshetra war was to kill Bhishma. In another version, despite the garland she was never biologically viewed as a man even considering her belief and practice. Nearing the war, Shikandi had sought a yaksha, Sthunakarna, who helped her by offering to exchange their sexes for a period of time. Thus, she had become biologically male.

Here this allowance to interchange her sex was seen as a boon, but just like that there are various instances in the mahabharata that the change was seen as a curse. In Monkey Man, Alpha recalls this divide with the dialogue “The police are looking for you. All over town. But not here. They find us too unsettling.” Arjuna was cursed by Urvashi that he would lose his masculinity when he rejected her advances — making him spend a year as ‘Brihannala’ during their exile. Ila is another feature, She was born to Vivasvata Manu and his wife Shraddha who wished for a male offspring. They prayed and the gods changed Ila to a man called Sudyumma. The story goes on to Sudymma going into a forest where he is cursed to become a female but the curse is mitigated by Shiva who allows him to be a male every alternate month. During his female phase, Ila/Sudyumma consummated her marriage with Budha.

Evidently, these tales are written as evidence of transgender prevalence rather than as involvement. Similarly in monkey man too, although the inclusion of the hijras weren’t out of distaste they felt to serve more as a plot device rather than fully fleshed-out characters to the story. They aren’t portrayed one dimensionally, their fight and reasons were well communicated, especially as we watch one of the people in the community assaulted and the rest find the courage to stand up. However given the short runtime and focus on Patel’s arc the script fails to delve any more into complexities of their lived experiences and instead, it felt like their struggles were better used as background material to enhance the narrative, ultimately relegating them to the sidelines of the story. This is still not to say that the movie tries to score points with inclusion ‘for the sake of it’ ; they predominantly make it a note to first show the community’s art and wisdom, their loved experiences for sharing jokes and music, just as much as the other person. It is only after that the movie delves into the marginalisation and violence they face and their reason to fight.

This feat is not to be marvelled at any more than normal, regardless of the deep-rooted presence of transsexual individuals in Hindu mythology as divine figures and heroes, they continue to face various forms of ostracism. One of the first references of transgender is the female avatar of Vishnu, Mohini. In the Mahabharata, Aravan, the son of Arjuna and Ulupi was offered to be sacrificed for Goddess Kali to ensure the Pandavas victory in the Kurukshetra war. Aravan’s only request was to spend the last night of his life as a married man. No woman was willing and came forward to marry Aravan only to be a widow the following day. Hence, Krishna assumes his form as Mohini and marries him.

The Hijra community in Tamil Nadu identifies themselves as Aravanis, named after Aravan, their progenitor. This cultural association is deeply rooted in the mythological narrative surrounding Aravan. In the village of Koovagam, Tamil Nadu, an annual 18-day festival is held to commemorate Aravan’s sacrifice. During this festival, trans women from the village dress up as Aravan’s wives and participate in rituals mourning his death. Only in recent years efforts have been made to provide them with the social support and opportunities for community integration that they deserve.

Since the Indian Supreme Court’s recognition of transgender people as a third gender in 2014, progress has been made in safeguarding their rights. Specifically with the enactment of the The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) in 2019, although it still contains restrictive provisions, such as the certification requirement for gender recognition, which is realistically not accessible to attain for most. Especially considering the community’s stagnant economic empowerment. Even with legal strides, social stigma persists, impeding the full inclusion of transgender individuals in Indian society. There is not even the basic respect that was awarded to them in Ayodhya, in today’s Delhi. Heavy discrimination in employment, healthcare, and housing persists, often leading to violence and plain fear. Nonetheless, advocacy efforts led by groups and activists i.e., National Legal Services Authority and Laxmi Narayan Tripathi continue to challenge stereotypes. Now with films putting in the bare minimum to portray more than documentaries and cautionary tales, there is so much more hope moving forward.